Table of contents

Introduction

Crabs have become unlikely heroes in protecting coral reefs from one of their biggest threats. Scientists at The University of Queensland and the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) made a remarkable finding – these small crustaceans actively hunt and eat young crown-of-thorns starfish, a notorious coral predator . A single crab can eat more than five young starfish each day .

The discovery carries huge weight for reef conservation efforts. Scientists found fewer young starfish in areas where more crabs lived. This provides strong evidence that these true crabs naturally help control starfish populations . These coral ecosystems have always been home to porcelain crabs and other true crab species, but scientists overlooked their role as natural control agents.

The sort of thing I love about these coral guard crabs deserves a closer look. This piece will break down their unique traits, how they live, and the ways they reproduce. We’ll also explore how these small but mighty reef defenders shape coral conservation’s future and what their presence means for reef ecosystems.

Biological Traits of Coral Guard Crabs

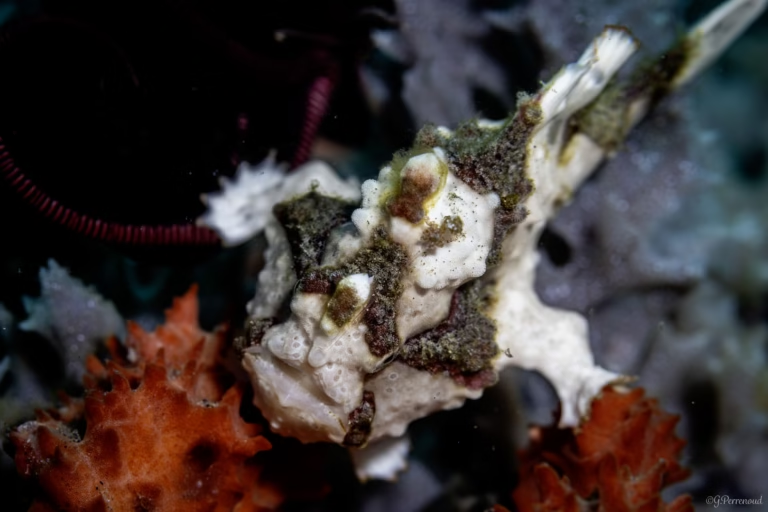

Coral guard crabs, especially when you have those from the genus Trapezia, show unique physical features that help them thrive among coral branches. These true crabs grow to about 5 cm in width and have a distinctively patterned trapezoidal carapace [1]. Species like Trapezia rufopunctata stand out with their mottled pattern of 100-200 reddish or orange spots on a white or pink background. This pattern gives them the name “rust spotted guard crab,” and they have striking green eyes [1].

The crab’s body has four pairs of walking legs and large, flattened clawed legs called chelipeds [1]. These body parts help them move through complex coral structures and defend their territory.

These crustaceans’ waterproof exoskeleton composed primarily of chitin protects them effectively [2]. This natural armor combines highly mineralized chitin-protein fibers in a unique “twisted plywood” or Bouligand pattern [2]. Their exoskeleton has many pore canal tubules that transport nutrients and strengthen its structure [3].

You can easily tell males and females apart in these crabs. Males have larger chelipeds that they use to defend territory, curb threats, and perform mating rituals [4]. Females develop wider abdominal pleons that help them attach and incubate eggs [4]. These crabs live as male-female pairs in coral colonies, and the number of pairs grows along with the colony [5].

Lifecycle and Behavior in Coral Habitats

Coral guard crabs reproduce through internal fertilization, and females carry fertilized eggs under their abdomen until they hatch into free-swimming nauplius larvae [6]. These larvae float in the water column as plankton and can spread across wide areas, but scientists haven’t determined how long this planktonic phase lasts [6].

The larvae go through multiple planktonic stages before they settle on the reef and transform into juvenile crabs [7]. These young crabs find suitable coral hosts and start their lifelong symbiotic relationship.

These crabs are highly adaptable omnivores. They eat coral mucus, detritus, and bacteria from coral tissues [6], but research shows they consume many other things too. Scientists who studied their intestinal contents found traces of a lot of different foods [8].

The crab’s specialized feeding structures include setae on the crab legs and maxillipeds (appendages near the mouth) that work as food brushes and combs [8]. These anatomical features let them both filter feed and scrape for food.

Guard crabs might be small, but they fiercely protect their territory. They defend their coral hosts from any intruders [9] and use their strong claws to fight off threats, so both the crabs and their coral homes benefit in this classic example of mutualistic symbiosis.

Ecological Role in Coral Reef Defense

The relationship between guard crabs and corals shows how species work together to survive on reefs. Scientists studying crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) outbreaks found that corals without Trapezia flavopunctata faced 64% attack rates while protected corals saw only 18% [10]. Protected coral colonies lost just 2% of their tissue compared to 22% in unprotected ones [10].

Different guard crab species have their own ways of protecting corals. Research in French Polynesia showed how Trapezia crabs use their unique traits to defend their host corals [10]. The crab’s size determines its role – smaller crabs fight off coral-eating snails, and larger ones take on COTS [11].

Scientists found that having different types of guard crabs creates multiple defense layers that help protect coral reefs over time [11]. The protection goes beyond just one coral – researchers found 61 colonies of 13 coral species that survived only because they were near P. eydouxi (red-eyed xanthid crab) communities during COTS attacks [10].

These tiny defenders make a big difference. Corals lost their largest protector (coral crab) to scientists and became starfish food overnight [11]. The crabs fight back by pinching the starfish’s tube feet and sometimes attack its stomach lining [12]. But even this defense system has limits – well-protected corals give in to attacks from many predators that gather as other food sources become scarce [13].

Conclusion

Scientists have discovered that coral guard crabs actively seek young crown-of-thorns starfish, changing our view of reef ecosystems. These crustaceans are vital biological control agents against significant threats to coral reefs, consuming several starfish daily. Their relationship with coral hosts exemplifies nature’s brilliance, as both species support each other’s survival—corals gain protection while crabs receive nourishment and shelter. This collaboration shows co-evolution’s role in resilient ecosystems.

Biodiversity is crucial for reef systems, with various crab species providing multiple layers of protection. Maintaining healthy crab populations is essential for safeguarding coral reefs globally. Conservation efforts should encompass not just corals but also the fragile partnerships that exist. Research shows reefs with strong crab populations suffer less damage from crown-of-thorns outbreaks.

However, these protective systems have limits against large-scale predator attacks. While guard crabs are strong defenders, they cannot protect corals indefinitely from overwhelming threats, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive ecosystem protection approach. Coral guard crabs remind us that effective conservation requires understanding the interactions among all elements, illustrating how nature’s collaborations can help preserve coral reefs for future generations.

FAQ

Q1. How do coral guard crabs protect coral reefs? Coral guard crabs actively hunt and consume juvenile crown-of-thorns starfish, which are notorious coral predators. A single crab can devour more than five juvenile starfish daily, helping to control starfish populations and protect coral reefs from damage.

Q2. What is the ecological significance of coral guard crabs? These crabs play a crucial role in maintaining reef health by defending their coral hosts from various threats. Their presence is associated with lower numbers of juvenile starfish, indicating they may naturally keep starfish outbreaks under control and contribute to the overall resilience of coral reef ecosystems.

Q3. How do coral guard crabs interact with their coral hosts? Coral guard crabs have a mutualistic relationship with corals. They live among coral branches, feeding on coral mucus, detritus, and bacteria. In return, the crabs fiercely defend their coral hosts from intruders and predators, benefiting both themselves and the corals in a symbiotic partnership.

Q4. What unique physical characteristics do coral guard crabs possess? Coral guard crabs typically reach about 5 cm in width and have a distinctive trapezoidal carapace. Some species, like Trapezia rufopunctata, display a mottled pattern of reddish or orange spots on a white or pink background. They have four pairs of walking legs and large, flattened clawed legs called chelipeds for navigation and defense.

Q5. How does the diversity of coral guard crabs benefit reef ecosystems? The diversity of coral guard crab species creates multiple layers of protection for coral reefs. Different crab species vary in size and defense capabilities, allowing them to tackle various threats. Smaller crabs defend against coral-eating snails, while larger specimens can fend off crown-of-thorns starfish, contributing to the overall resilience of reef ecosystems.

References

[1] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezia_rufopunctata

[2] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5553559_Structure_and_mechanical_properties_of_crab_exoskeletons

[3] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18299257/

[4] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8048398/

[5] – https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(23)01490-2.pdf

[6] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11836902/

[7] – https://marine-freshwater.fandom.com/wiki/Guard_Crab

[8] – https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ivb.12449

[9] – https://redseacreatures.com/taxon/invertebrate/crustaceans/crabs/red-spotted-guard-crab

[10] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4183949/

[11] – https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/smithsonian-scientists-discover-coral-s-best-defender-against-army-sea-stars

[12] – https://oceana.org/marine-life/crown-thorns-starfish/

[13] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5806057/